Shear or friction? Understanding shear in pressure ulcers

Part 1: The effects of shear forces in pressure ulcer development

A pressure ulcer can be defined as localised damage to the skin and/or underlying tissue, usually over a bony prominence (or related to a device), resulting from sustained pressure (including pressure associated with shear) (EPUAP, 2019). The damage can present as intact skin or an open ulcer and may be painful (NHSi, 2018). The effects of prolonged mechanical loads (pressure) on the skin and underlying tissue cause tissue deformation, which can result in occlusion of blood and lymph vessels leading to tissue necrosis or death.

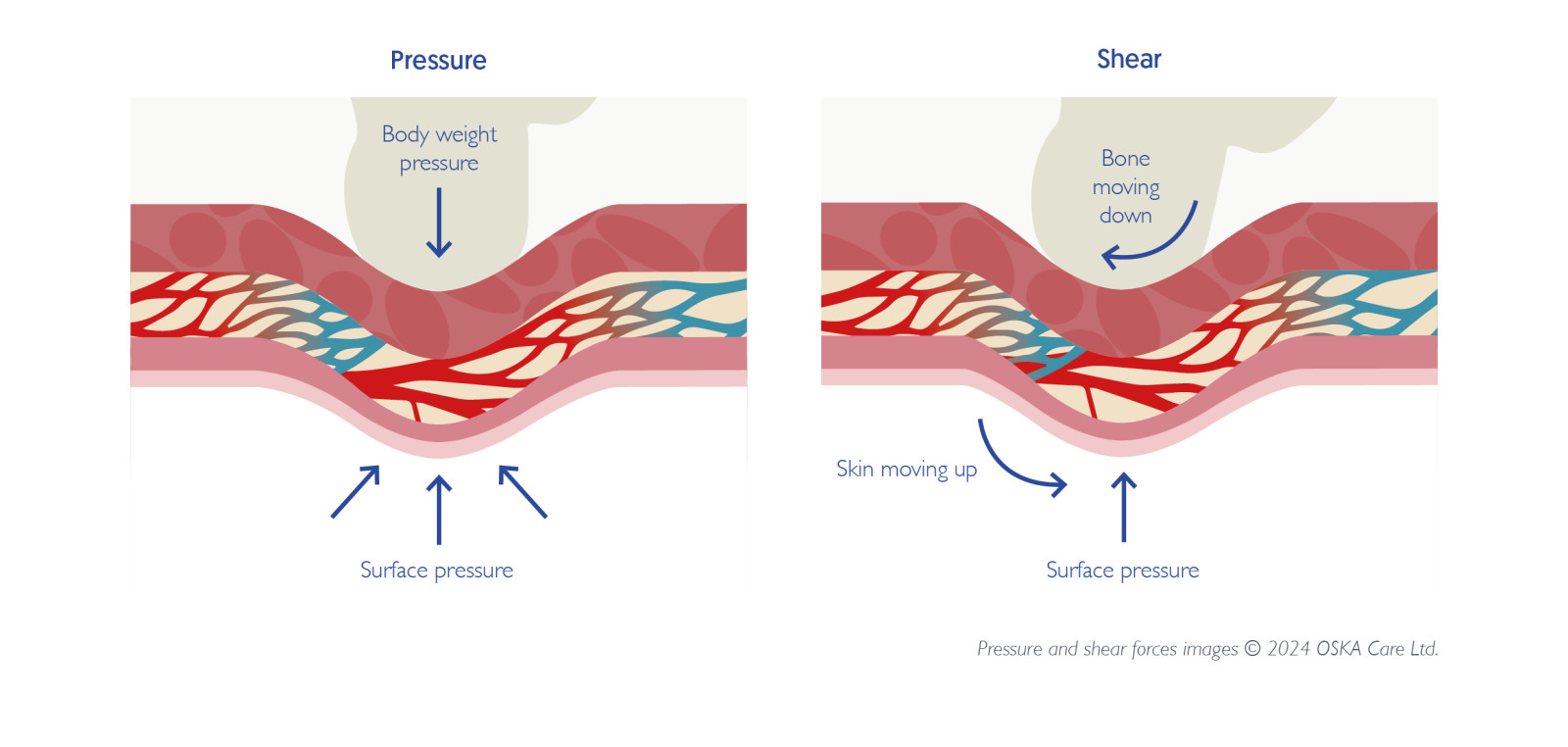

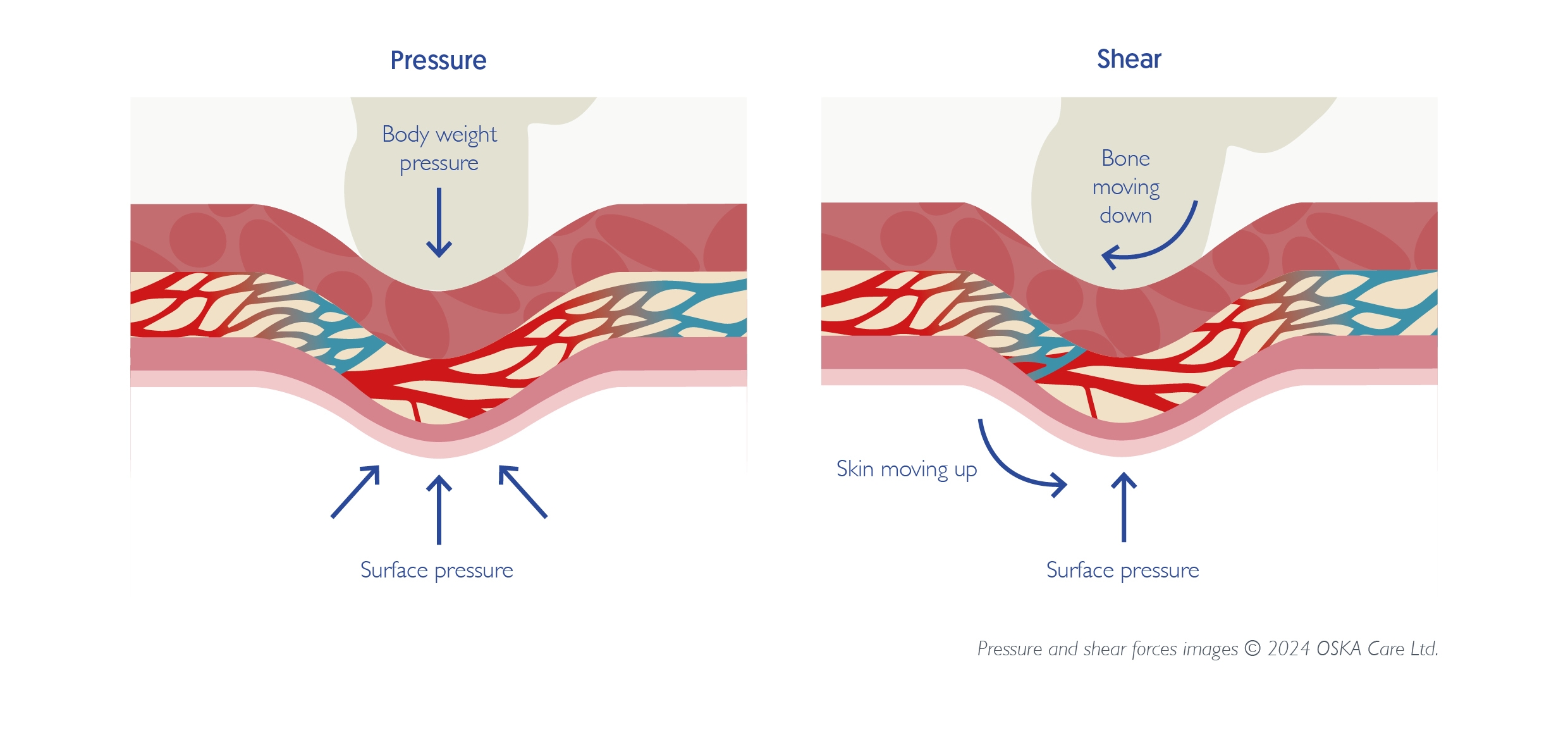

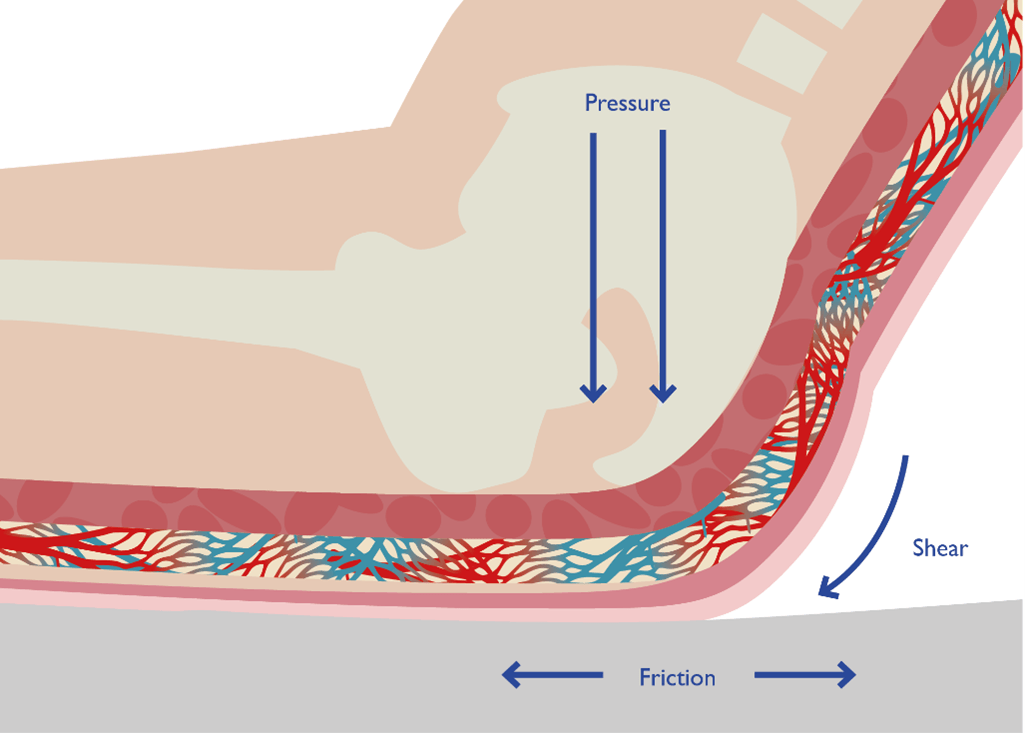

Shear is identified as a contributing factor to tissue deformation and injury (WHO, 2024. Endsjo, 2019). Prolonged mechanical loading often occurs in areas of the body where skin, vessels, subcutaneous fat or muscle are compressed and sheared between a stiff internal structure (bone or tendons) and a support surface (chair, cushion, mattress or medical device) and this often occurs over the most vulnerable bony prominence areas such as the sacrum and heels (EPUAP, 2019). Therefore, if we are to effectively prevent pressure ulcers, we need to carefully consider the effects of shearing and how these effects can be reduced on the body.

Shear force is “an action or stress resulting from applied forces which causes or tends to cause two contiguous internal parts of the body to deform in the transverse plane” (Lange, 2018). This force causes a bony prominence to move across the tissue as the skin is held in place (EPUAP, 2019). For example, when a patient is sat in a chair, friction will hold the skin in place but if the chair is not the correct height, then gravity will push down on the patient’s body causing the bone to slide down as the skin and soft tissues get dragged against the chair.

Shear forces can happen when a patient stays in a static seated position or the body moves, even slightly, against the material within a cushion or mattress and against the resistance of the cushion cover itself. Shear can also occur during recline, when the seat to back angle opens and disrupts alignment with body surfaces. Much of a power reclining system design is an attempt to reduce this shear as much as possible (Lange, 2018).

Unfortunately, the ability to measure shear is very difficult and in most cases, it is unclear how exactly shear forces damage tissues. Shear forces happen even when a person is lying completely flat and any change in their position will create shear both internally and externally. If pressure remains constant and shear forces increase, tissue deformation will also increase. As a result, current research does not inform us as to which clients are at greater risk of shear injury (Lange, 2018).

When pressure and shear forces are applied in combination, the tissue that lies between the body structures and the chair will be squeezed, whilst the internal structures will be distorted and stretched, resulting in severe pressure damage (Brodrick et al, 2021). The effects of shear can also be seen when a patient is sat up in bed without an appropriate knee break facility, or when a patient is being repositioned in bed, independently moving whilst in bed, or getting out of bed (EPUIAP, 2019).

Fig.1: Pressure and shear force © 2024 OSKA Care Ltd.

Fig.2: Pressure and shear force © 2024 OSKA Care Ltd.

Evidence suggests that there are several basic requirements a support surface must meet in order to help reduce the effects of shear on the body.

- Firstly, the support surface must help to reduce shear caused by patient movement, and secondly, reduce the effects of moisture on the skin (EPUAP, 2019).

- The presence of moisture on the skin is known to exacerbate the effects of friction on the skin, effectively making the skin “more sticky” and thus prone to the damaging effects of shear (Shaked & Gefen (2013).

- Mattress covers that are designed to be moisture vapour permeable enable air to circulate through the cover material and around the patient’s body reducing heat build-up and subsequent perspiration. This in turn helps to maintain the skin microclimate and reduce the effects of shear.

- Mattress covers that have a multi-stretch fabric work to reduce the potential effects of shear by enabling the cover to conform to the patient’s body and move with the patient as they move reducing the effects of shear and friction.

- The incorporation of ‘anti-shear’ zones within the cover can also work to reduce the effects of shear from patient movement. The anti-shear zones within the OSKA Series5 cover design are located at the 3 most vulnerable areas of the body – the heels, sacrum and scapula. These silicone coated, shear-minimising fabric bands prevent these vulnerable areas from “digging into” the surface upon movement and have a gliding effect to ensure that micro and macro shear forces are reduced, transferring shear to more shear tolerant anchoring points thereby ensuring patient stability when being moved.

With the combination of pressure and shear potentially leading to the most severe pressure damage, support surfaces which can help to reduce the damaging effects of shear whilst also providing good levels of immersion and envelopment, must be considered by clinicians as part of a holistic approach to pressure ulcer prevention.

Please cite as: OSKA Care Ltd. (July 2025). Shear or friction? Understanding shear in pressure ulcers Part 1: The effects of shear forces in pressure ulcer development. Havant, Portsmouth: OSKA Care Ltd.

References:

- NHS Improvement (2018) Pressure Ulcers: revised definition and measurement. Summary and Recommendations. NHS Improvement, London. 2018. Available online: NSTPP-summary-recommendations.pdf (england.nhs.uk). Accessed 9 June 2022

- Endsjo, A. (2019) Pathways of wounds: shear vs pressure. [Online] Pathway of Wounds: Shear vs Pressure (permobil.com) Accessed 18 October 2022.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, Alliance PPPI, (2019). Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline. The International Guideline.

- Carver, C. (2016) Pressure Injury Prevention: Managing Shear and Friction, Wound Source, blog, [Online] https://www.woundsource.com/blog/pressure-injury-prevention-managing-shear-and-friction Accessed 6 June 2022.

- Broderick, V. V., Cowan, L. J., Haley, J.A., (2021) Pressure Injury Related to Friction and Shearing Forces in Older Adults, Journal of Dermatology and Skin Science. 3 (2) pp. 9-12.

- Lange, M. (2018). Shear. Available at DIRECTIONS-2018v5_MedFocus-1.pdf

- Loeper JM et al: (1986). Therapeutic positioning and skin care, Minneapolis. Sister Kenny Institute. Types of skin damage and differential diagnosis | Musculoskeletal Key

- Shaked, E., Gefen, A. (2013) Modelling the Effects of Moisture-Related Skin-Support Friction on the Risk for Superficial Pressure Ulcers during Patient Repositioning in Bed, Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology,1 (9) pp. 1-7

- World Health Organization (2024). EH90 Pressure ulceration.