The Fundamentals of Care Framework

‘Care’ can be seen as a broad concept which is not restricted to, but often epitomised, by the nursing profession. Fundamental care requires that the actions of the care giver are one of respect and focuses on the person’s essential needs to ensure their physical and psychosocial wellbeing (Mudd, et al 2020).

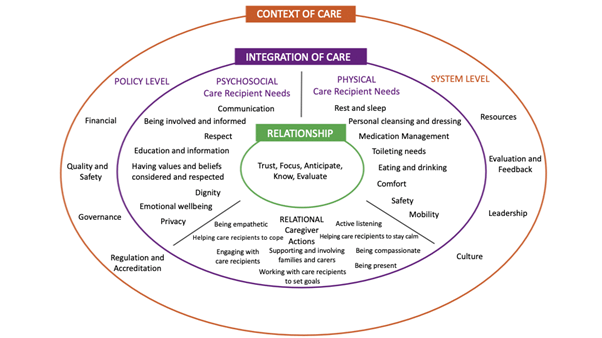

The Fundamentals of Care Framework (often shortened to FoC Framework) is a conceptual framework which was developed in 2012 as part of an international learning collaborative to define, guide, and evaluate what “fundamental care” means in nursing and how it should be delivered in clinical practice, education, and leadership. It has arisen partly in response to long‑standing concerns that fundamental care tasks (such as help with eating, toileting, hygiene, relationship, emotional support etc.) are often neglected, under‑valued, or treated as discrete tasks rather than as integrated elements of holistic, person‑centred nursing (Mudd et al 2020. Kitson et al, 2013).

The FoC Framework highlights the importance of nurses and other healthcare professionals building trusting, therapeutic relationships with patients and their families or carers. It also stresses the need to address and connect individuals’ various fundamental needs – including physical needs like nutrition and mobility, and psychosocial needs such as communication, privacy, and dignity – through relational behaviours like empathy and active listening. Additionally, the FoC Framework recognises that the care environment must enable and support healthcare providers to form these relationships and effectively meet patients’ integrated needs (ilccare.org. 2025).

The Framework, outlined in Fig.1, highlights 3 core dimensions for the delivery of high-quality fundamental care:

Fig 1. © 2025 International Learning Collaborative https://ilccare.org/the-fundamentals-of-care-framework/

Applying the dimensions of the Framework to pressure ulcer care

1. Nurse-Patient relationship

A strong, trusting relationship between nurse and patient is essential for pressure ulcer prevention and management. Such relationships support open communication, allow patients to express discomfort, changes in skin, pain, or mobility issues, and promotes patient engagement in preventative measures (e.g. repositioning, nutritional intake). For example, the study How experienced wound care nurses conceptualize what to do in pressure injury management (Lee & Chang 2023) shows that experienced nurses emphasise listening to patient reports of discomfort and integrating patient reported observations into care decisions. This reflects relational components of FoC where active listening, empathy, and trust help ensure that needs are identified early and addressed.

Moreover, when the nurse‑patient relationship is positive, patients are more likely to adhere to repositioning schedules, report early skin changes, or be motivated to engage in care (e.g. moisturising skin, avoiding pressure), rather than simply being passive recipients.

2. Integration of physical, psychosocial, and relational needs (care provider’s actions)

Pressure ulcer care is often viewed in physical/technical terms (e.g. risk assessment, wound dressings, support surfaces). The FoC Framework argues that for care to be wholly inclusive, the psychosocial and relational needs must be woven in, not treated as extra or optional.

- Patient education and involvement: a systematic review of patient education by Thomas et al in 2022 showed how structured educational interventions was deemed to help improve patient knowledge and participation and quality of life. Educating patients (and carers) enables them to be active partners in prevention and management (e.g. repositioning, skin inspection).

- Physical needs: risk assessment (e.g. using validated risk assessment tools alongside clinical judgement), appropriate and patient-centred repositioning, suitable support surfaces, skin care, moisture management, ensuring nutrition and hydration. A cross-sectional study of nursing interventions in acute care found that risk and skin status assessment, repositioning, support surfaces, and nutritional care are commonly applied and are critical components in prevention programmes (Tervo-Heikkinen, et al. 2023).

- Psychosocial and relational needs: ensuring dignity, privacy, emotional support. For example, patients may feel shame or fear in exposing their skin or having wounds exposed. Building relationships during provision of care includes explaining what is being done and why, involving patients, carers and families in creating the care plans, respecting preferences and concerns.

3. Context of care

The environment where care is provided plays a crucial role in determining whether pressure ulcer care aligns with the principles of the Framework. This encompasses factors such as staffing levels, workload demands, availability of resources (like pressure-relieving equipment and dressings), leadership support, organisational policies, workplace culture, physical setting, documentation practices, and staff education (Kitson, A.L. 2018).

Context of care barriers

- Inadequate staffing and skill mix – high patient-to-nurse ratios mean essential care like repositioning or skin assessments may be delayed or missed.

- Lack of access to equipment – limited availability of good quality pressure-relieving mattresses, cushions, or moisture management tools/ products can impede preventive care.

- Poor leadership or organisational support – when prevention is not prioritised at the management level, frontline nurses may lack the guidance or encouragement to implement best practice.

- Inconsistent education and training – without regular updates, nurses may lack current knowledge on evidence-based strategies for pressure ulcer prevention (Tubaishat et al., 2018).

- Cultural issues – in healthcare settings where pressure ulcers are viewed as unavoidable or not a priority, prevention may not be actively pursued.

Context of care facilitators

- Supportive leadership and safety culture – managers who prioritise prevention, monitor outcomes, and provide positive feedback, foster better care practices.

- Adequate staffing and time – when workload is manageable, nurses are more likely to complete necessary repositioning, inspections, and documentation.

- Accessible equipment and technology – ready availability of support surfaces, moisture barriers, and other tools, enables prompt and effective care.

- Regular education and training – ongoing high quality, up-to-date, competency-based training ensures staff stay updated on risk factors, early signs, and new interventions (Moore & Price, 2004).

- Auditing and feedback – systems that track pressure ulcer rates, identify missed care, and provide regular feedback, can improve adherence to fundamental care principles.

Conclusion

In conclusion, applying the Fundamentals of Care (FoC) Framework to pressure ulcer prevention and management can highlight the importance of addressing not only the care receivers’ physical needs, but also the relational and psychosocial aspects of their care.

Key barriers such as time constraints, inadequate staffing, limited resources, and task-oriented cultures often hinder effective pressure ulcer care (Feo et al., 2017; Tubaishat et al., 2013). However, by facilitating strong nurse–patient relationships, holistic assessments, leadership support, and regular education we enable the care givers to deliver comprehensive, person-centred care that aligns with the principles of the FoC Framework (Kitson et al., 2018). When these elements are present, nurses are better equipped to prevent pressure ulcers, respond to patient needs in a dignified manner, and ensure that fundamental care needs are not missed.

Please cite as: OSKA Care Ltd. (November 2025). The Fundamentals of Care Framework. Havant, Portsmouth: OSKA Care Ltd.

References

Feo, R., Conroy, T., Jangland. E., Muntlin Athlin, Å., Brovall, M., Parr, J., Blomberg, K., & Kitson, A. (2017). Towards a standardised definition for fundamental care: A modified Delphi study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27, 2285-2299. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14247

Kitson, A. L. (2018) ‘The Fundamentals of Care Framework as a Point‑of‑Care Nursing Theory’, Nursing Research, 67(2), pp. 99‑107. doi:10.1097/NNR.0000000000000271.

Lee, Y. N. and Chang, S. O. (2023) ‘How experienced wound care nurses conceptualize what to do in pressure injury management’, BMC Nursing, 22, Article 189. doi:10.1186/s12912‑023‑01364‑z.

Moore, Z., & Price, P. (2004). Nurses’ attitudes, behaviours and perceived barriers towards pressure ulcer prevention: Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13(8):942-51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00972.x.

Mudd, A. Feo, R., Kitson, A. and Conroy, T. (2020) ‘Where and how does fundamental care fit within seminal nursing theories: A narrative review and synthesis of key nursing concepts’, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(19–20), pp. 3605–3616. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15420

Tervo-Heikkinen, et al. (2023) ‘Nursing interventions in preventing pressure injuries in acute inpatient care: a cross‑sectional national study’, BMC Nursing, 22, Article 198. doi:10.1186/s12912‑023‑01369‑8.

Thomas, D. C., Chui, P. L., & Yahya, A., Wen, J.W. (2022) ‘Systematic review of patient education for pressure injury: Evidence to guide practice’, Worldviews on Evidence‑Based Nursing, 19(4), pp. 267‑274. doi:10.1111/wvn.12582.

Tubaishat, A., Aljezawi, M., & Al Qadire, M. (2013). Nurses’ attitudes and perceived barriers to pressure ulcer prevention in Jordan. Journal of Wound Care, 22(9):490-7. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2013.22.9.490

Image credit

Image obtained from https://ilccare.org/the-fundamentals-of-care-framework/

Content within image derived from 1) Kitson, A., Conroy, T., Kuluski, K., Locock, L., & Lyons, R. (2013). Reclaiming and Redefining the Fundamentals of Care: Nursing’s Response to Meeting Patients’ Basic Human Needs. School of Nursing, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia. Available from: https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/2440/75843/1/hdl_75843.pdf; and 2) Feo, R., Conroy, T., Jangland. E., Muntlin Athlin, Å., Brovall, M., Parr, J., Blomberg, K., & Kitson, A. (2017). Towards a standardised definition for fundamental care: A modified Delphi study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27, 2285-2299. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14247