Shear or friction? Understanding shear in pressure ulcers – Part 2a: The importance of repositioning patients effectively

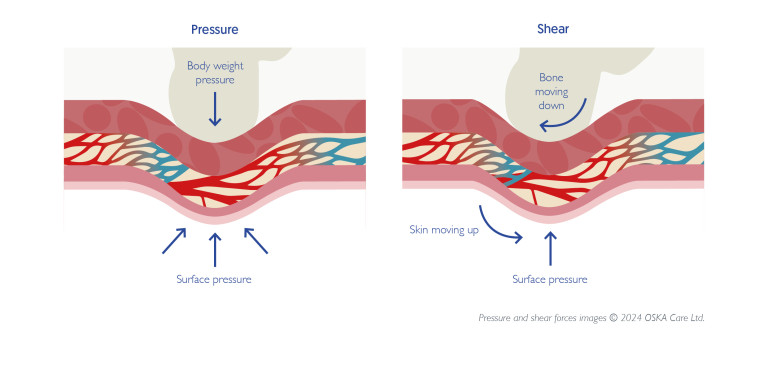

The European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP, 2025) reminds us that although the causes of pressure ulcers are multifaceted, they cannot occur without mechanical loading and forces acting on the skin and underlying tissue. It then goes without saying that extended periods of sitting or lying on one area of the body, without redistribution or repositioning, can lead to tissue deformation and ultimately tissue hypoxia or death. This then re-emphasises how fundamental the actions of repositioning and mobilisation are for preventing and managing numerous complications associated with immobility, such as pressure ulcers.

While repositioning could be considered a straightforward, effective and safe process, it does require a multidisciplinary approach to ensure we consider not only the patient’s physical condition, but also the expertise of the healthcare workers, the availability of appropriate manual handling equipment, and any input from specialist teams around positioning or offloading requirements.

This article will look at some of the factors that must be considered to ensure patient repositioning is conducted safely, effectively, and with patient comfort at the centre of the care planning. It will discuss some of the biomechanical principles we need to be aware of for repositioning, the assessment of patient-specific needs, the use of appropriate equipment and techniques, the importance of education and training for healthcare professionals, and the organisational factors that contribute to successful repositioning practices.

Good Practice Statement

“It is good practice to reposition individuals at risk of pressure injuries regardless of the type of pressure redistribution full body support surface being used.

The interval between repositioning might be adjusted depending on the pressure redistribution capabilities of the support surface and the individual’s response.

However, no support surface can entirely replace repositioning.”

EPUAP, 2025

1. Understanding biomechanical principles and minimising force

The well known ‘2-hourly repositioning’ became the gold standard in an era of healthcare (1950s -1980s) which is very different to where healthcare is now. Currently our patients are living longer, have more comorbidities, are frailer, and wait longer while our services are busier, less staffed and more complex (Hanna et al, 2016). According to EPUAP (2025), repositioning at 2- or 3-hourly intervals may be appropriate for most individuals at risk of pressure ulcers, provided they are also using a suitable full-body pressure redistribution support surface. Importantly, they suggest NOT routinely extending repositioning intervals to four, five or six hours for individuals at risk of pressure ulcers. EPUAP (2025) do suggest that progressive extension of intervals between repositioning may be appropriate for patients who are improving and whose risk of developing pressure ulcers is decreasing.

Before any healthcare worker (HCW) attempts to reposition a patient, it is important they understand some of the biomechanics involved to help to reduce friction and minimise the physical strain on both the patient and HCW (Sato, 2019). Lifting patients vertically places immense stress on the HCW’s spine and increases the risk of injury. Instead, all HCWs should employ techniques that utilise lateral transfer aids – specialised equipment, including but not limited to:

- mechanical lifting devices (hoists)

- slide sheets

- lateral air transfer devices

- turn systems/devices

- low friction fabrics

- and turn-assist features on beds or mattresses

along with manual handling techniques e.g., ergonomic techniques, two- to four-person lifts, etc. that reduce the risk of friction and shear which should be available and implemented (EPUAP, 2025. Waters, 2018).

These devices distribute the patient’s weight over a larger surface area, allowing for smoother and more controlled movement. Moreover, understanding the patient’s centre of gravity is crucial. Repositioning close to the patient’s centre of gravity allows for better control and stability, reducing the risk of falls or sudden, uncontrolled movements (Hignett et al., 2013).

Applying excessive force or twisting motions during repositioning can lead to musculoskeletal (MSK) injuries in both the HCW and patient (Garg et al., 2014). Training programmes should emphasise proper body mechanics, including maintaining a wide base of support, bending at the knees rather than the waist, and keeping the patient close to the body (Waters, 2018).

Good Practice Statement

“It is good practice to reposition the individual in such a way that optimal offloading of pressure points and maximum redistribution of pressure are achieved.”

EPUAP, 2025

2. Patient assessment and individualised care plans

Effective repositioning cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. A thorough assessment of the patient’s individual needs and limitations is essential. A pressure ulcer risk assessment tool (such as PURPOSE-T, Waterlow, Braden) should be used to identify patients at high risk for pressure ulcers. These tools identify risk factors such as sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear (Lyder et al., 2012).

Based on the risk assessment, holistic assessment, and skin assessment, an individualised care plan should be developed, outlining the frequency and method of repositioning, as well as any specific precautions, contraindications or equipment (Edsberg et al., 2016). Consider the individual and any informal carers or HCWs when developing a repositioning regime to meet that individual’s needs (EPUAP, 2025).

The repositioning plan should be regularly reviewed and updated based on the patient’s changing condition. Furthermore, patient preferences should be considered whenever possible, promoting autonomy and improving the overall patient experience. This requires open communication and a collaborative approach between the healthcare team, the patient, and their family members.

Things to consider:

- Evaluating the patient’s physical capabilities, such as their range of movement, strength, and balance, as well as their cognitive status and overall medical condition (Nijs et al., 2017).

- Seek specialist advice if additional equipment is needed such as postural support, specialist mattresses, wheelchairs, splints etc., especially if the individual is at high or long-term risk of developing pressure ulcers.

- Assess the individual’s pain and comfort level prior to and after repositioning and give analgesia if required to make the process more comfortable and achievable.

- Repositioning needs to be a 24-hour plan and should include when patients sleep, lie down, sit up, or time spent in other equipment such as a wheelchair, transport chairs or stretchers, bath, slings and hoists (EPUAP, 2025).

- When using any positioning device, make sure that they are not positioned in such a way that applies further pressure on vulnerable areas (i.e. pillows directly against the sacrum).

- Patients with spinal cord injuries (SCI) require specific repositioning techniques to avoid further injury and their needs may change over time and be required long term.

- Patients with respiratory conditions may benefit from specific positioning strategies to optimise ventilation, or they may need to be in a seated position for lengthy periods of time, which may require higher risk level equipment to be in place and the dynamics of tissue (Lyder, 2012).

Good Practice Statement

“It is good practice to assess for signs of early skin and tissue damage that may mean the individual requires more frequent positioning or preferential positioning off damaged areas.”

EPUAP, 2025

3. Using appropriate equipment and techniques

The availability and proper use of manual handling devices are essential for safe and effective patient repositioning. In addition to lateral transfer aids, devices such as hoists, turning wedges, and specialist mattresses can significantly reduce the physical demands on HCWs and improve patient comfort (Collins et al., 2015). Turning wedges and pillows can be used to maintain patients in specific positions, alleviating pressure on bony prominences and promoting optimal alignment (Moore & Patton, 2019).

However, simply having access to equipment is not enough. HCWs need to be adequately trained in the proper use of each device. This includes understanding the device’s capabilities and limitations, as well as adhering to the manufacturer and local safety protocols (Waters, 2018).

The best technique for repositioning also depends on the patient and the availability of resources and staff numbers. For example, the “logroll” technique is often used for patients with spinal injuries, while a lateral transfer with a slide sheet is frequently employed for patients at risk of pressure ulcers (Moore & Patton, 2019). Regardless of the technique used, it is essential to prioritise patient comfort and dignity.

Good Practice Statement

“It is good practice to use specialised equipment designed to reduce friction and shear when repositioning individuals. If manual handling is necessary, techniques that minimise friction and shear should be applied.”

EPUAP, 2025

Things to consider (EPUAP, 2025)”

- The choice of equipment should be tailored to the patient’s individual needs and the specific task in hand. Ask each patient about their previous experience with manual handling and repositioning as some equipment or techniques may cause fear, increase pain or discomfort.

- Clear communication with the patient throughout the process is crucial, explaining what is happening and ensuring they feel safe and secure.

- Avoid any dragging when repositioning to avoid shear damage – pay particular attention to heel areas.

- Do not leave equipment under the patient (i.e. slings under patients when sitting out) unless it has been specifically assessed as appropriate and low risk and is designed for this purpose.

- Remember that turn assist equipment such as tilting devices, beds or mattresses does not allow the body’s posterior to be fully free of pressure or contact with the support surface so interval repositioning and skin assessment will still be required.

- Patients who can self-reposition should be assessed for any assistive devices (slide boards, slide sheets or lift bars) that they need to promote and maintain their mobility. It is important that any assistive devices are always easily accessible to them.

- For children or young people, it is important to ensure the devices used are suitable for them, for their age, weight and complexities.

- In a patient’s own home, you will need to work with the carers, encourage and educate on independent movement where possible in between carer visits, and ensure the equipment works with the layout of the home environment.

- Regular equipment maintenance is also essential to ensure proper functioning and prevent malfunctions that could lead to injury.

Good Practice Statement

“It is good practice to initiate frequent, small and incremental shifts (micromovement) in body position for critically ill.”

EPUAP, 2025

Please cite as: OSKA Care Ltd. (August 2025). Shear or friction? Understanding shear in pressure ulcers Part 2(a): The importance of repositioning our patients effectively. Havant, Portsmouth: OSKA Care Ltd.

References

Collins, F., Drogt, E., & Hignett, S. (2015). The effectiveness of interventions to prevent musculoskeletal injuries and reduce the manual handling burden in healthcare: A systematic review. Applied Ergonomics, 51, 173-183.

Dean, E. (2015). Physical therapy versus exercise for the treatment of acute or chronic respiratory conditions. Cardiopulmonary Physical Therapy Journal, 26(1), 7-12.

Edsberg, L. E., Black, J. M., Goldberg, M., McNichol, L., Moore, L., & Sieggreen, M. (2016). Revised national pressure ulcer advisory panel pressure injury stage classification system. Journal of Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing, 43(6), 585-597.

Garg, A., Kapellusch, J. M., Hegmann, K. T., Thiese, M. S., Moore, J. S., Bernard, B. P., & Lifestyle Risk Factor Consortium. (2014). The effectiveness of interventions to prevent work-related musculoskeletal disorders. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46(6), e103-e124.

Hanna, D.R., et al. (2016). Learning about turning: Report of a Mailed Survey of Nurses’ work to reposition patients. MedSurg Nursing. Vol 25, (4). Pg 219-223.

Hignett, S., Crumpton, C., Ruszala, S., Davies, C., & Sims, W. (2013). Evidence-based patient handling: Tasks, equipment, and interventions. Routledge.

Lyder, C. H., Ayello, E. A., Cuddigan, J., et al. (2012). National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Journal of Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing, 39(1), 9-19.

Moore, Z. H., & Patton, D. (2019). Positioning and repositioning for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2019(7).

Nijs, J., Logghe, I., Coppieters, I., et al. (2017). Pain neurophysiology education improves cognitions, pain thresholds, and movement performance in people with chronic whiplash: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 54(2), 109-124.

Sato, T. (2019). Biomechanics of lifting and transfer tasks: Implications for prevention of back injuries. Journal of Occupational Health, 61(1), 1-14.

Waters, T.R. (2018). When is it safe to manually lift a patient? American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 61(7), 559-575.