Back 2 Basics: Top Tips for Pressure Ulcer Prevention

This clinical article has authored to follow up OSKA, the Pressure Care Experts’ 30 minute The Pressure Refresher: back to basics of pressure ulcer prevention webinar on 20 November 2025 to support the National and International Stop The Pressure Day.

Pressure ulcers remain high on the healthcare agenda and make up approximately 7% of all wound types within the UK population, alongside being one of the top 10 harms occurring to patients within healthcare settings. They cause significant pain, anxiety, distress and increase the risk of morbidity to those affected. They are responsible for consuming high levels of resources, time and cost to both patients and organisations. (Young, 2024).

Below are 10 evidence-based Top Tips for preventing pressure ulcers in UK clinical practice, drawing exclusively on peer-reviewed nursing journals published within the last 10 years.

1. Provide and attend ongoing staff education and training

Continual professional development significantly enhances nurses’ knowledge, skills and competence in the prevention of pressure ulcers. Providing education which covers skin assessment, risk assessment, surface selection, skin integrity, and prevention strategies, in line with the recommended aSSKINg care bundle (NHSi, 2018) can significantly improve patient outcomes and practice adherence (Kandula et al., 2025). It is also important that this education is supported through up-to-date local pressure ulcer prevention policies and links to national and international guidance. Ongoing staff education will also help to maintain clinical competencies and enhance awareness.

Visit the OSKA Academy to find out what’s available: https://oska.uk.com/oska-academy/

2. Holistic assessment using a validated, structured risk assessment tool

It remains key to use evidence-based assessment tools as part of a holistic assessment to identify patients at risk of developing pressure ulcers. Structured assessments, like PURPOSE-T, Waterlow or Braden, enhance early identification of at-risk patients, which is key to prevention (Peart et al., 2025). They are evidence-based assessment tools which should be used as part of a holistic assessment and should be completed on admission, at regular intervals, and when a patient’s condition changes or deteriorates. These tools help to identify key risk factors which increase risk (immobility, nutrition, moisture, skin integrity) and help with proactive care planning and prevention interventions. Collier and Jones (2023) emphasise that systematic risk assessment supports targeted interventions and aligns with NICE and EPUAP guidelines. https://epuap.org/

3. Skin moisture management

The presence of moisture, in any form, does not directly cause pressure ulcers and does not ‘turn into’ a pressure ulcer(s). However, the constant presence of moisture, whether it is sweat, urine, saliva, stomal leakage, and wound exudate, causes the skin cells to swell, become macerated and weak (Young, 2024). When this happens, and unrelieved pressure is applied to this area, the risk of skin breakdown is higher and quicker. Effective management of Moisture Associated Skin Damage (MASD) is essential and information about MASD should be included in any education around pressure ulcer prevention.

The first line management of incontinence is the promotion of continence such as regular toileting, encouraging self-management where possible, setting reminders, or ensuring the right equipment is close by if mobility is an issue. The management of sweat may require a reduction in room temperature and the use of fans alongside good hygiene and the appropriate use of barrier products and sweat absorbing pads.

Wound exudate needs to be assessed as to the cause and managed appropriately, and if problematic, then the Tissue Viability Service should be contacted for a review. Any leakage from stoma product, affecting the patient’s skin, should be referred to the local Stoma care nurse specialist.

4. Regular repositioning regimes

Regardless of the support surface that is in place, it is very important to assess your patient’s independent mobility and care plan for how often they may need assistance with repositioning. Pressure ulcers occur due to prolonged pressure caused by immobility or staying in the same position for a prolonged period (Young, 2024). This may include patients with mental health issues, lethargy, apathy or medications which cause drowsiness or in maternity settings where epidurals are performed or patients who have brain degenerative disorders who might just forget that they need to move. Harris et al. (2023), stress that evidence is still emerging on frequency and best methods of repositioning but NICE (2015) recommends that immobile patients are repositioned every 2–4 hours even if they have a pressure-relieving device. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs89/chapter/quality-statement-5-advice-on-repositioning

5. Choice of support surface

Selecting appropriate support surfaces is critical for patients at risk of pressure ulcers. There are four key factors what contribute to reducing individual risk factors:

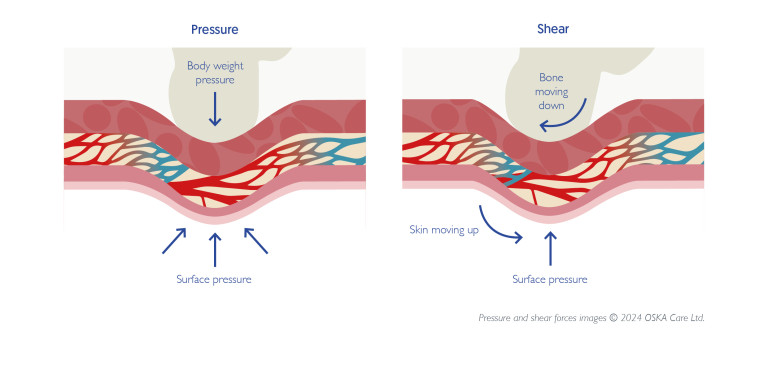

- Immersion & envelopment – by increasing the contact surface area and redistributing weight, the pressure is reduced.

- Microclimate management – reducing the chance of heat buildup and sweating helps lower the risk of pressure damage.

- Shear & friction reduction – reducing these two major contributing factors to pressure damage is important. Some systems like the OSKA Series5 have integrated anti-shear zones. https://oska.uk.com/you-ask-we-answer/

- Alternating pressure – changing the areas of pressure every 5-10 minutes enables reperfusion of the blood vessels. Micro-shifts mimic the regular movements of a healthy body.

EPUAP guidelines emphasise that continuous use of appropriate surfaces reduces incidence and when integrated with risk assessment tools and repositioning protocols, 24-hour support surfaces represent a clinically sound and economically sustainable approach to pressure ulcer prevention (EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019).

6. Prioritise Nutrition & Hydration

Prioritising nutrition and hydration is essential in pressure ulcer prevention, as malnutrition and dehydration significantly increase a patient’s risk by impairing skin integrity and delaying tissue repair (Fletcher, 2020). It is essential that a comprehensive nutritional assessment, using MUST (https://www.bapen.org.uk), should be undertaken for all at-risk patients. Individualised nutrition care plans should include fortified diets or supplementation where needed (Fletcher, 2020; McCoulough, 2023). Adequate hydration supports oxygen and nutrient transport, promoting wound healing and reducing complications (Green, 2022). Evidence shows that well-nourished patients have lower ulcer incidence, highlighting the need for proactive, multidisciplinary interventions in clinical practice (EPUAP et al., 2019).

7. Foster a wider support/MDT network and practice

It is important to establish a wider network of support to ensure there is a holistic approach to preventing pressure ulcers. Collier and Jones (2023) advocate the involvement of Tissue Viability Nurses, physiotherapists, dieticians, General Practitioners, and staff with more in-depth knowledge and skills in pressure ulcer prevention (link nurses, PU champions, senior clinicians) to help align prevention strategies and to ensure all the patients’ needs are met. This can also be extended to involve educators, commercial company support with education and equipment selection and district nursing teams.

8. Monitor outcomes through audits and quality improvement (QI) projects

Regular audits allow healthcare teams to track incidence, prevalence, and adherence to prevention protocols, identifying gaps in care delivery (NHS Improvement, 2018). Quality improvement initiatives, such as root cause analysis (RCA) and benchmarking, support continuous learning and promote evidence-based interventions. Data-driven monitoring not only enhances accountability but also informs staff education and resource allocation, ultimately reducing pressure ulcer rates and improving patient outcomes (NICE, 2014). Kandula et al. (2025) also highlight that structured feedback loops were vital to engaging staff in audits and QI projects and make them feel part of the process.

Please cite as: OSKA Care Ltd. (December 2025). Back 2 Basics: Top Tips for Pressure Ulcer Prevention. Havant, Portsmouth: OSKA Care Ltd.

References

Collier, M. & Jones, S. Glendewar, G., (2023). Pressure ulcer prevention, patient positioning and protective equipment. British Journal of Nursing, 32(3) Pg: 108-116. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2023.32.3.108

European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA) (2019) Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline. Available at: https://epuap.org/pu-guidelines/ (Accessed: 20 November 2025).

Fletcher, J. (2020) ‘Pressure ulcer education 7: supporting nutrition and hydration’, Nursing Times, pp. 1–6. Available at: https://cdn.ps.emap.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/03/200311-Pressure-ulcer-education-7-supporting-nutrition-and-hydration.pdf (Accessed: 20 November 2025).

Green, K. (2022) ‘Hydration and pressure ulcer prevention: a pilot study’, Wounds UK. Available at: https://wounds-uk.com (Accessed: 20 November 2025).

Harris, C., Entwistle, E. & Batty, S., 2023. Repositioning for pressure injury prevention in adults: a commentary on a Cochrane review. British Journal of Community Nursing, 28(Sup9):S5-S12. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2023.28.Sip9.S8

Kandula, U. R. (2025). Impact of multifaceted interventions on pressure injury prevention: a systematic review. BMC Nursing, 24, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02558-9

McCoulough, S. (2023) ‘Nutrition & hydration and its importance in pressure ulcer prevention’, Oska UK. Available at: https://oska.uk.com/nutrition-hydration-its-importance-in-pressure-ulcer/ (Accessed: 20 November 2025).

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE), (2015). Pressure Ulcers, Quality Standard No 89. London, NICE.

NHS Improvement (2018). Pressure ulcer core curriculum. Available at chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Pressure-ulcer-core-curriculum.pdf

NHS Improvement (2018) Pressure ulcers: revised definition and measurement. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk (Accessed: 20 November 2025).

Peart, J., Myers, H., Devlin, A. & Barnes, J., (2025). Improving pressure ulcer prevention knowledge to reduce avoidable harm. British Journal of Nursing, 34(12), pp. S20-S28. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2024.0409.

Wood, J. et al., 2019. Reducing pressure ulcers across multiple care settings using a collaborative approach. BMJ Open Quality, 8(3), e000409.

Young. C,. (2024). Pressure Ulcer Prevention Handbook: A clinical reference guide for care homes & Hospices. Havant, Portsmouth, OSKA Care Ltd.